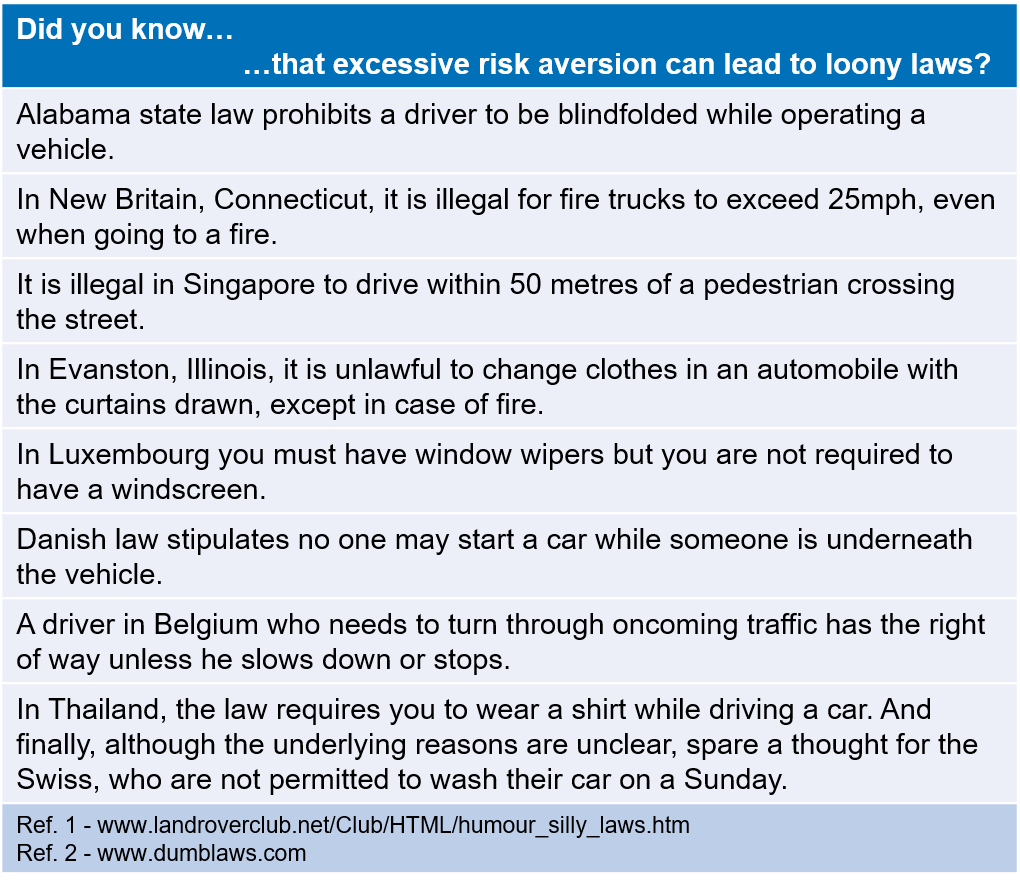

Excessive risk aversion

HAS RISK MANAGEMENT GONE TOO FAR?

For the villagers of Bromham, this year’s St George’s Day should have been greeted with a hearty English breakfast to raise funds for a local primary school. Instead, according to the Daily Mail on 24 April [Ref. 1], the event was cancelled at the last minute because of health and safety concerns about untrained volunteers preparing fried eggs. More specifically, it would seem that local county council guidelines regarding the storage and preparation of food were being rather zealously enforced.

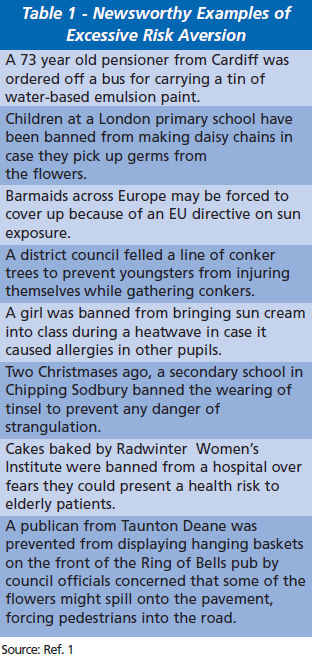

The news article provoked colourful reaction from the volunteers themselves, the general public and Tory MP, Philip Davies, who said, “It is barmy that parents who want to celebrate St George’s Day and raise a bit of money for their local school are prevented from doing so by ridiculous rules and regulations.” The next day the Chief Executive of the UK’s Health & Safety Executive (HSE), Geoffrey Podger, wrote to the Daily Mail to make it clear that the HSE were not involved, and “have no interest in making people extensively risk averse” [Ref. 2]. What this and other similar stories portray (see Table 1) is a society where risk is not necessarily balanced by reward in the decision making process.

CAUSE FOR CONCERN?

Although the underlying reasons for excessive risk aversion are clearly case-specific, the root causes seem to fall into one or more of four general categories:

- Fear of litigation or other adverse personal consequences.

- Dogmatic reluctance to depart from policy or question its relevance or derivation.

- Belief that risks should be eliminated entirely.

- Convenient excuse, masking a potentially unpopular reason.

Indeed, the HSE are so concerned that they are promoting a debate on where the sensible balance lies in health and safety, with the aim of ensuring that resources are deployed on risks that could cause serious harm [Ref. 3]. As part of this initiative, a web forum was held from July to October 2005. Its principal findings were:

- The public’s perception of risk is sometimes skewed: there appears to be great fear of certain hazards with tiny associated risk, while other more serious risks are tolerated.

- Although excessive risk aversion does occur (as supported by Table 1), disproportionate decisions are the exception rather than the rule.

- The evidence for a growing ‘compensation’ culture is far from clear, especially given that studies consistently show a fall in the level of claims. However, the perception of such a culture could amplify risk aversion.

- Although there was a general consensus that risks often could not be eliminated, there appeared to be disagreement in where the balance should be drawn between risk and cost.

As a result, the HSE has undertaken to:

- Commission research to establish the extent and causes of excessively risk averse decisions.

- Draft a set of sensible risk management principles.

- Revise some of its key risk management documents, such as “5 steps to risk assessment” to reflect that sensible risk management means assessment and control of risks, rather than eliminating all risks.

MEDIA EXCESS

The media clearly thrives on extremes, whether from too little or too much risk management. The truth, as usual, is probably somewhere in the middle – occasionally, there are hazards that merit less control and some that merit more. Judging from Table 1 and the outcome of the HSE’s risk debate, perhaps this situation is more common where the general public or public services are concerned. In business, though, especially major hazard industries, risk assessment coupled with decision making that balances risk with reward remains the key to sensible risk management.

While the nuclear and offshore industries have led the way, risk-based approaches can now be found in the fire & rescue services, the rail industry, marine safety, and occupational health & safety, for example.

PROFESSIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT

Wherever there is regulation or other drivers from industry to achieve cost-effective risk control, you will find risk professionals. Their role should be to bring discipline, structure and above all, pragmatism to the management of risks so that important risks are controlled well, trivial risks are discounted and resources are expended in a manner that is proportional to risk.

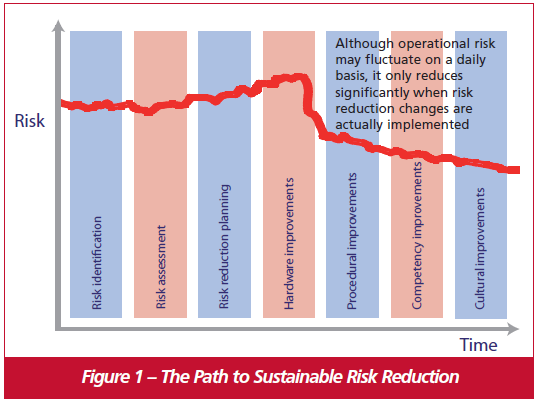

Traditionally, in the major hazards industries, risk assessment has involved extensive scientific and engineering research and analyses to gain an understanding of the nature of the hazard and its effect on plant, people and the environment. While this still remains the bedrock upon which informed decisions are made, analysis alone will not result in risk reduction (see Fig. 1). This requires tangible improvements to hardware and procedures, backed up by competency assurance initiatives, such as improved training.

Further improvement comes from a grass roots embedding of an active risk management culture into day-to-day activities. While this is easy to say, its implementation requires a concerted effort over an extended period of time. In identifying improvements, whatever their nature, the obligation of the sensible risk professional is always to seek maximum benefit from a finite budget.

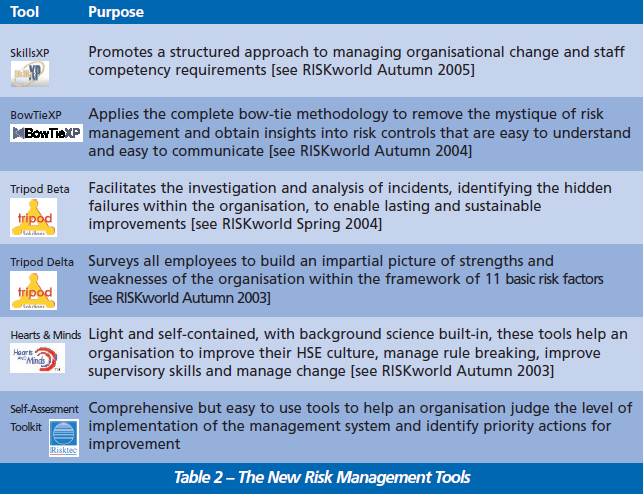

Although many of the supporting tools and techniques for sensible risk management are still developing, some of those used by Risktec are included in Table 2. Most notably, these have been designed with an emphasis on knowledge transfer and real risk reduction.

SUCCESS, NOT EXCESS

The media might have you believe in a society where excessive risk aversion is commonplace. While the truth is probably less sensational, there is some evidence of this type of behaviour. Businesses, especially those in the major hazard industries, cannot afford excessively risk-averse behaviour; neither can they afford to ignore significant risks. The answer is sensible risk management.

Ref. 1 – www.dailymail.co.uk

Ref. 2 – www.hse.gov.uk

Ref. 3 – www.hse.gov.uk/riskdebate

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 9.