The price of (single point) failure

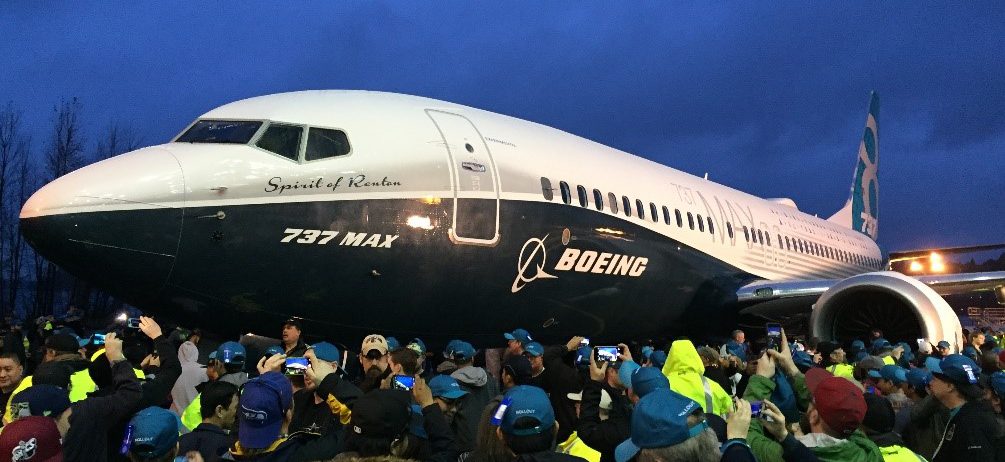

With two Boeing 737 MAX aircraft crashing in less than six months in seemingly identical circumstances and killing 346 people, there is a real sense that there is something wrong, not only with the aircraft design, but with safety culture at the company.

Preliminary accident data suggest the cause of the Ethiopian Airlines crash in March 2019 (Ref. 1) was essentially identical to the Lion Air crash in October 2018 (Ref. 2) – in both cases an automated control system known as the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) functioned erroneously, repeatedly forcing the nose down, with confused pilots ultimately unable to control pitch.

GRASSROOTS

The story of these catastrophes appears to be rooted at the very creation of the concept for the 737 MAX (Ref. 3). Challenged by the commercial pressure on market share posed by the latest Airbus A320neo (new engine option), Boeing had neither the time nor the money to develop an all-new aircraft (Ref. 4). Instead, Boeing settled upon a strategy for modification, once again, of their workhorse 737 airframe design – the 737 MAX is the fourth generation of this aircraft, which first flew in 1967.

An overarching requirement was for the incorporation of the very latest jet engines, guaranteeing a dramatic and genuinely competitive improvement in fuel efficiency. A further pillar of the marketing strategy for the 737 MAX would be that no additional training of flight crew should be necessary; demanding in turn that any changes to flight systems be both minimal and operate in the background without any need for pilot intervention. The incorporation of the new engines into the 737 MAX was not straightforward, on account of their sheer size in comparison to their forebears. The engines had to be mounted higher up and, as a consequence, further forward. This, critically, determined that under certain in-flight conditions the 737 MAX would tend to pitch upwards (Ref. 5).

OUT OF SIGHT

A brand new, additional flight system known as MCAS was therefore incorporated to run in the background, automatically adjusting the aircraft trim to ensure the aircraft handled in the same manner as earlier versions. Importantly, the MCAS system was designed to be so deeply integral to the control of the aircraft, beyond the influence of the crew, that it was not referred to in the flight manual. Prior to the crash of the Lion Air 737 MAX, pilots of the aircraft were unaware that it even existed.

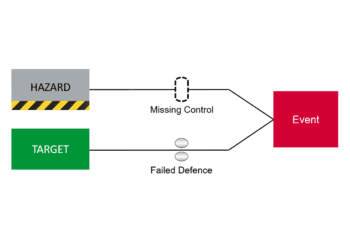

SINGLE POINT OF FAILURE

A flaw in the configuration of the MCAS appears to be its reliance on data from a single Angle of Attack (AoA) sensor (Ref. 5), even though the aircraft is equipped with two such sensors. These AoA sensors provide a measure of the pitch of the aircraft against which, together with other relevant flight data, the MCAS dynamically determines and implements optimum trim of the aircraft. The MCAS, despite being critical to the safety of the aircraft, was not resilient to a single point of failure. In both the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines 737 MAX disasters, it appears to have been a single failure of an AoA sensor that activated operation of the MCAS, with immediate knock-on effects upon instrumentation read-outs and cockpit alarms. The unfortunate crews faced contradictory indications and false warnings, from their port and starboard instrumentation respectively, including simultaneous warnings of air speed too high and too low (Ref. 5). The ultimate result in both cases was an unrecoverable downward pitch beyond the control of the pilots, leading directly to 346 fatalities. In the second quarter of 2019, Boeing provisioned $4.9 billion for airlines’ compensation. The final price tag is likely to be much, much higher.

CULTURAL FAILINGS?

From a safety engineering perspective, the configuration of the MCAS system is difficult to defend. Whilst born out of a perhaps ill-conceived concept design, it nonetheless survived the detailed design and assessment process, as well as internal and regulatory approval regimes. In particular, beyond the immediate forensic investigation findings, a broader malaise has become apparent in respect of the relationship between Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) responsible for the flight certification of its aircraft. A pivotal accusation against the FAA is that, lacking sufficient resources to discharge its duties directly, it has entrusted Boeing with a significant regime of self-inspection – genuine independent inspection is routinely absent. Instead “Authorised Representatives” (ARs), employees of Boeing, officially designated to act on behalf of the FAA, work to provide the necessary oversight. Notably, the managerial structure that supports the work of ARs has also changed, so that they are now both appointed by, and report to Boeing (instead of the FAA as of old). Quite simply, the ARs now no longer have anyone to safeguard their independence (Ref.6).

LESSONS TO BE LEARNED

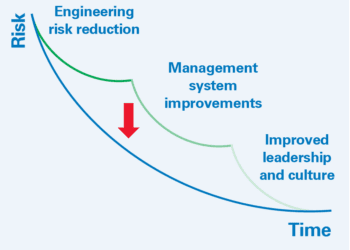

In the 1960s Boeing established itself as the leading passenger aircraft manufacturer in the wake of a series of crashes of the de Havilland Comet. Today, one cannot help but wonder if the aviation giant has fallen behind its peers in terms of continuous improvement. Perhaps modern aircraft design practice could benefit from best practice within other highly regulated industries – such as the incorporation of diversity into safety systems, alongside its existing and long-standing commitment to redundancy; and the use of independent technical assessment or peer review as part of a rigorous management of change process.

CONCLUSION

The loss of 346 lives caused by a single failure reveals as much about the safety culture at Boeing as it does about the flawed aircraft design. Moreover, it should give all safety engineering professionals across all industrial sectors pause to reflect on the adequacy of both our individual efforts and the wider cultural environment in which we work. As ever, the need to challenge the status quo and seek continuous improvement never sleeps.

References:

1. Preliminary aircraft accident investigation report, KNKT 18.10.35.04, Boeing 737-8 (MAX) PK-LQP, Republic of Indonesia, 29th October 2018.

2. Aircraft Accident Investigation Preliminary Report, AI-01/19, Ethiopian Airlines Group B737-8 (MAX) Registered ET-AVJ, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 10th March 2019.

3. BBC online news: What went wrong inside Boeing’s cockpit, 17th May 2019.

4. The New York Times online: Boeing was “Go, Go, Go” to beat Airbus with the 737 MAX, 23rd March 2019.

5. Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger III, Statement to the Subcommittee on Aviation of the United States House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure,