Chronic unease – the hidden ingredient in successful safety leadership?

Leaders working in high hazard industries are faced with a difficult personal challenge: how do you avoid complacency about major accidents such as a nuclear release, oil spill or train derailment, when such events rarely happen? How do you not ‘forget to be afraid’?

The importance of avoiding complacency when it comes to industrial safety risks has long been recognised, particularly in High Reliability Organisations (e.g. Ref. 1). One term that is now being used by the oil and gas industry to describe this important state of mind is ‘chronic unease’. This term actually appeared earlier in the literature than other related terms such as mindfulness, restless mind or safety imagination, when Professor James Reason introduced it as a ‘wariness’ towards risks as far back as 1997 (Ref. 2).

SO WHAT IS CHRONIC UNEASE?

Put simply, chronic unease is the opposite of complacency. It is a healthy scepticism about what you see and do. It is about enquiry and probing deeper, really understanding the risks and exposures and not just assuming that because systems are in place everything will be fine. It is not just believing in what you see or what you hear or what the statistics tell you. It is about resetting your tolerance to risk and responding accordingly and continually questioning whether what you do is enough.

The thought process of a leader therefore changes from “We haven’t had an incident, we are doing so well,” to “Is there anything we’re overlooking and what else do we need to do?”

ATTRIBUTES OF CHRONIC UNEASE

A recent research paper defines chronic unease as a state of psychological strain in which an individual experiences discomfort and concern about the control of risks (Ref. 3). That is, chronic unease is not driven by a concern about risks per se, but rather about the way these risks are managed and controlled.

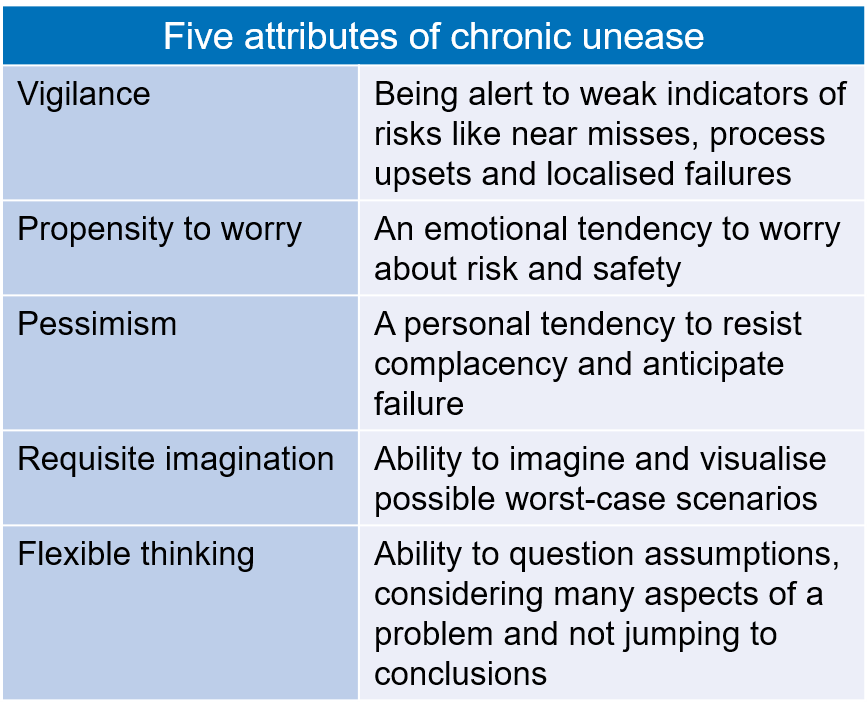

The paper identifies five attributes as the principal psychological components of this state of mind, see Box 1. The extent and likelihood of a leader to experience unease depend on these attributes.

The origin of unease starts with the leader’s perception of risks, which will be influenced by his or her vigilance and experience. Evaluating the degree of threat inherent in the risks is then determined by the individual’s personality characteristics, especially the propensity to worry, pessimism and the ability to imagine worst-case scenarios.

When leaders use chronic unease in their work it enables them to:

- Think flexibly

- Not jump to conclusions (“think slow”)

- Encourage employees to speak up

- Listen to others

- Be receptive to bad news

- Show safety commitment

THE NEW WORLD

So what will the world look like when we have created a sense of chronic unease which replaces complacency? (Ref. 4).

Leaders will ask the right questions. They will be keen to know what vulnerabilities exist. Safety specialists will respond in clear terms, which anyone can understand and relate to. Operators will understand their role in safety management and will be encouraged to speak about their real safety concerns, without fear of repercussions.

Leaders will actively seek information which tells them where attention needs to be paid to address the vulnerabilities. There will be a positive desire to learn from others and to share knowledge and experience, so that lessons do not have to be re-learned time and time again in different organisations. Collaboration and information sharing will replace unhelpful turf protection.

Corporate lawyers would also be challenged to help leaders communicate and share, rather than stand in the way of sharing and learning. Systems safety knowledge and competence will be recognised as fundamental for all leaders within the major hazards industries.

WHAT’S THE DOWNSIDE?

Chronic unease might raise (in hindsight) unnecessary concerns, and it might slow decision-making processes. But this should be weighed against the impact of not taking action or making poor decisions – a major accident.

CONCLUSION

Research indicates that chronic unease is a desirable state for leaders at all levels in relation to the control of risks. When leaders are using chronic unease they will have developed a culture where they are alert to even the weakest signals of potential failure, and make effective and timely interventions.

References

1. Managing the unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity, Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001.

2. Managing the risks of organisational accidents, Reason, 1997.

3. Chronic unease for safety in managers: a conceptualisation, Fruhen, Flin and McLeod, 2013.

4. Process safety, focusing on what really matters – leadership, Hackitt, 2013.

This article first appeared in RISKworld issue 25