Black swan or blind spot? The duality of extreme events

A black swan is characterised by Nassim Nicholas Taleb [Ref. 1] as an event which:

- Is a surprise (to the observer), an ‘extreme outlier’

- Has a major impact

- Is rationalised by hindsight, as if it could have been expected

The phrase ‘black swan’ was a common expression in 16th century London as a statement of impossibility, on the presumption that all swans must be white because all historical records of swans reported that they had white feathers. But black swans were then discovered in Western Australia in 1697.

The phrase today is often rolled-out when there is a crisis, such as a major industrial accident, natural disaster or corporate financial collapse. But is this always strictly correct? For example, was the Fukushima nuclear accident a black swan?

FUKUSHIMA – A BLACK SWAN?

On the 11th March 2011, having survived a powerful Magnitude 9 earthquake (the largest recorded in Japanese history), the reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant were shut down safely only to be compromised by the 14-15m tsunami that hit the site about one hour later, leading to core meltdown. But how does the Fukushima accident score against Taleb’s three criteria?

1. SURPRISE? NO

At up to 15m in height the tsunami was larger than the ‘design basis event’ of 3.1m, but over the last 100 years Japan’s east coast has suffered a number of large tsunami (>10m) associated with earthquakes; with more than one locally over 15m.

2. MAJOR IMPACT? YES

While no site workers or members of the public were killed by the nuclear release, an exclusion zone of 20km radius still exists around the reactor site and 100,000 people were displaced from their homes. Germany, Italy and Switzerland declared their intention to halt current nuclear programmes. The site is no longer operational, leaving a long-term shortfall in electricity generation of around 2% of Japan’s needs. In the short-term, nearly all of Japan’s nuclear power plants were unavailable whilst safety reviews were being undertaken, with a loss of 30% of the country’s electricity generation.

3. RATIONALISED? YES

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) identified that design basis tsunami for the Fukushima site underestimated the hazard, based on the accepted methods and the available data [Ref. 2]. The assumption that the site would definitely stay ‘dry’ (rather than be flooded) was not demonstrated, and represented a ‘cliff edge’ in terms of consequences. A series of ‘Stress Tests’ have subsequently been performed on all reactor sites across Europe, examining scenarios significantly beyond their design basis to determine the response to extreme events and identify if there is a ‘cliff edge’. No fundamental weaknesses have been found.

OR BLIND SPOT?

Assessing other industrial major accident events against these three criteria similarly shows that while they tend to have an extreme impact and are rationalised by hindsight, they are rarely a surprise. Rather, they are actually organisational ‘blind spots’.

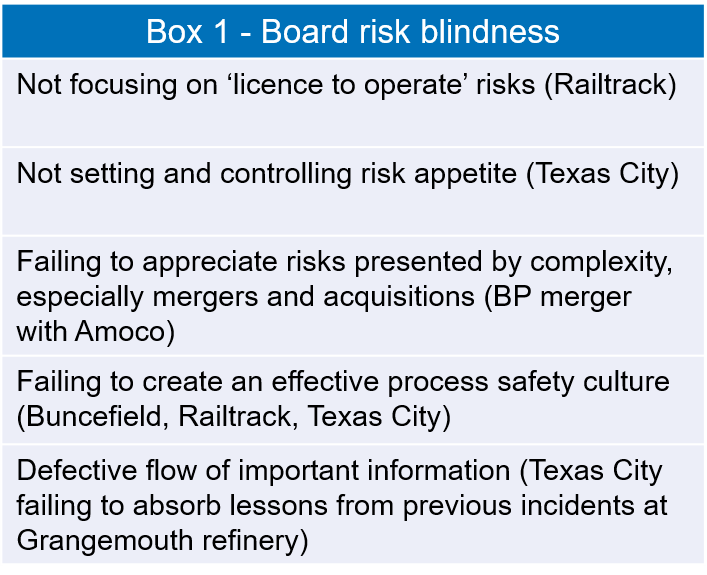

A recent study of 18 high profile corporate crises [Ref. 3], which included the Texas City explosion and the Buncefield fire of 2005, as well as the Great Heck, Hatfield and Potters Bar rail accidents of 2000-2002, concluded that ‘Board risk blindness’ was one of 7 underlying causes of these crises. This blindness manifests itself in various ways (see Box 1). The study concluded that several developments are necessary to address these risks effectively, including the need for boards to recognise the importance of risks that are not identified by current approaches, as well as focus on how to ensure missing risks are captured.

CONCLUSION

Many industrial major accidents are colloquially described as black swans, when in fact they were entirely foreseeable and preventable if it were not for organisational blindness. While shining light on those risks that are hard to see is not necessarily simple, a good place to start is to foster a culture that has a ‘collective mindfulness’ of such risks.

References

1. The Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2010.

2. Report on IAEA International Fact Finding Expert Mission of Fukushima NPP Accident Following Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, 2011.

3. Roads to Ruin, AIRMIC, 2011.

This article first appeared in RISKworld Issue 21